Regina Caeli – Queen of Heaven, Rejoice!

The Regina Caeli, Latin for “Queen of Heaven,” is a hymn and prayer ...

T

Second only perhaps to pastors, catechists are more likely than any other parish staffer to encounter questions about canon law. This is because catechists, especially those working with adults seeking to convert, are recognized as accessible sources of information about virtually all aspects of the Catholic Church. Most cradle Catholics, having grown up with a vague awareness of the presence of canon law-however incomplete and even erroneous their understanding of Church law might be-are much less likely to pose questions about the operation of canon law unless, perchance, they find themselves directly affected by it. Not so with candidates for conversion; they are motivated to ask questions about all facets of Church life.

So parish catechists could make good use of a basic grounding in canon law; where do they find it? Fortunately, information on canon law is much easier to obtain now than was the case not too many years ago. This trend is likely to continue, moreover, as a wider awareness of canon law leads the faithful to appreciate the fact that canon law does affect their lives as Catholics. This article will provide an overview of what canon law is and then will identify some resources for catechists seeking a more detailed understanding of the subject.

Briefly put, canon law is the internal legal system of the Catholic Church. Canon law has everything one would expect to find in a mature legal system: laws, courts, cases, judges, lawyers, and so on. Canon law affects, to one degree or another, virtually every aspect of Catholic life, sometimes much more intimately than many people realize; other times, though, much less directly than one might have otherwise thought.

Historically, canon law is the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the western world. Fortunately, throughout Church history some of the world’s finest legal, theological, and pastoral minds have contributed to the formation of canon law, all trying to serve one goal, that expressed in the final norm of the Code, Canon 1752: “…having before one’s eyes the salvation of souls, which is always the supreme law of the Church.”

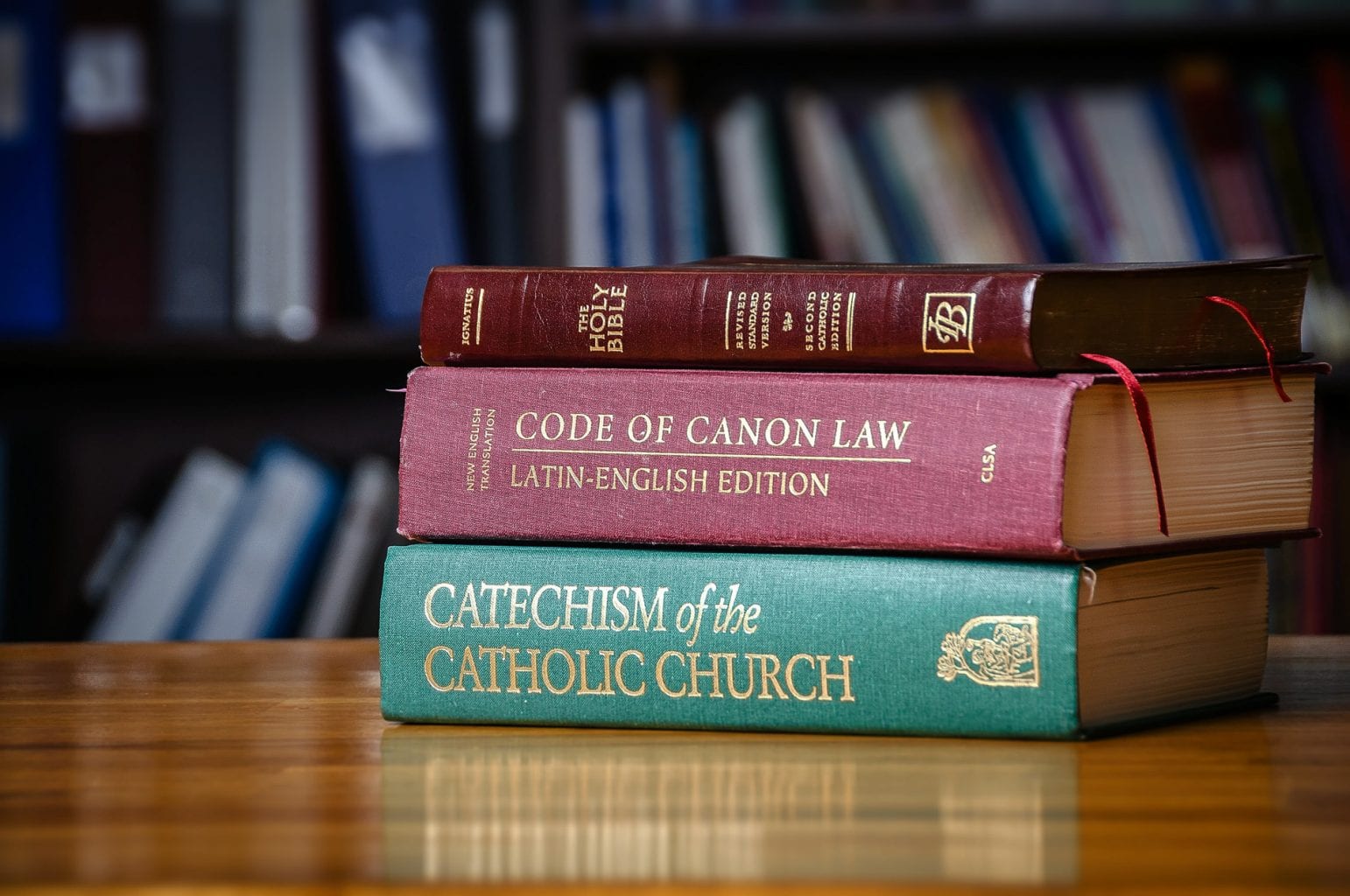

Today, canon law for Roman Catholics is found primarily in a single volume called the 1983 Code of Canon Law. (Eastern Catholics have a separate code which was issued in 1990.) The date indicated, 1983, while not technically part of the official title, simply refers to the year in which the current canon law took effect, replacing when it did so the Catholic Church’s first Code of Canon Law which was published in 1917. Up until this century, the canon law of the Catholic Church was scattered over a wide variety of texts and collections which only an elite group of highly-trained specialists could access. The modern redaction of Church law into a single unified code, however, is one of the steps which has contributed to the ability of rank-and-file Catholics to make greater use of canon law in their own lives.

A Look Inside

The 1983 Code consists of 1,752 canons or rules, divided into seven topics, or “books.” Considering that this single volume regulates most of the juridical aspects of the faith life of some 750 million Roman Catholics around the world, the brevity of the 1983 Code (which is even shorter than the 1917 Code’s 2,414 canons!) is a remarkable achievement.

The official language of the 1983 Code of Canon law is Latin, a choice retained from the 1917 Code because of the long tradition of precision which Latin brings to ecclesiastical thought and writings. As a practical matter, however, the actual provisions of canon law are now available, for the most part reliably, in various modern language translations. This too represents a change in approach from that taken under the 1917 Code. The Holy See now permits responsible parties to prepare and publish translations of canon law, providing thereby another spur to the growth of interest in and use of Church law among the faithful.

Catechists in the United States should be aware of two English translations of the Code of Canon Law, one prepared by the Canon Law Society of America and available in a very convenient Latin-English format, the other prepared by the Canon Law Society of Great Britain and Ireland. While the British version does not offer the parallel Latin text, it does have a much better index of topics, which is sold separately. Among Spanish translations of the 1983 Code, that prepared by Salamanca faculty in Spain and published by Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos is quite good. All of these translations of the Code of Canon Law are priced very reasonably. Most parishes already have at least one of the versions in their libraries.

Of course, the text of the 1983 Code itself will always be the first place one turns for answers to canonical questions. But it will not be surprising to learn that canon law, like every other advanced legal system, has developed over the centuries a technical vocabulary and certain methods of expression which at times go beyond the words of the written text. These nuances and implications are not always apparent upon an untrained reading of the canons, and yet they can greatly affect the meaning and application of canon law in Church life. Therefore, commentaries prepared by scholars and practicing canonists are a good place to look for more detailed explanations of the law.

Both the Americans and the British (the latter with the help of several Irish and Canadian canonists) have prepared lengthy, canon-by-canon commentaries on the 1983 Code: see J. Coriden, T. Green, & D. Heintschel, eds., The Code of Canon Law: A Text and Commentary, (Paulist Press: New York/Mahwah, 1985, with 1,152 pages); and Canon Law Society of Great Britain & Ireland, The Canon Law: Letter & Spirit, (Liturgical Press, Collegeville, MN: 1995, with 1,060 pages). In Canada, moreover, catechists might look for E. Caparros, et al., eds., Code of Canon Law Annotated (Wilson & Lafleur: Montreal, 1993, with 1,629 pages), which is a fine English language version of a commentary originally developed by the University of Navarra in Spain but adapted for use in North America.

These books are somewhat pricier than the plain codes, of course, but with any luck one’s parish library will have already obtained at least one of these important works. Most arch/diocesan tribunals have all of these works. Whenever using any commentary, however, remember that the canonical opinions expressed therein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily “official.” The 1983 Code of Canon Law itself makes clear that the only binding interpretations of the canons are those which come either from the pope himself, or from a relatively short list of persons qualified and appointed by the pope to give authentic interpretations (see Canon 16).

Canon Laywers

A few words should now be said about the source to which, as a practical matter, most people will turn first for answers to questions on Church law: canon lawyers. In times past, it could pretty well be assumed that anyone ordained would have studied a fair amount of canon law in the seminary. That is less true these days. Now, when one speaks of a canon lawyer, one means a degreed specialist in canon law, whether ordained or lay. The 1983 Code of Canon Law reserves most official positions in canon law to those having licentiates or doctorates in canon law, although exceptionally well-qualified persons can serve as canonical advocates (“lawyers”) in certain cases.

In answer to a very common question, most canon lawyers are not civil lawyers, and the differences between, not just the two legal systems, but the very ways each has of approaching legal issues, are significant. On the other hand, nearly all canon lawyers are expected to have a solid grounding in theology since, as we have seen, canon law must be based on Church teaching in order to serve any useful purpose.

The quality of the canonical opinion one gets from a canon lawyer will depend on all the usual things: the educational background of the canonist, his experience in the precise subject matter, and so on. I mention this because, in the not too distant past, there seemed to be the perception that all canon lawyers were equally qualified to offer opinions on all questions of Church law, and that their answers were going to be equally reliable. That is simply not the case today, if it ever was.

So much, then, for an overview of canonical resources. It is time now to turn our attention to a consideration of the role of law in the life of the Church.

It is no secret that a severe wave of antinomianism (that is, a rejection of any place for law in the life of faith) swept through the western Church following the Second Vatican Council. Fortunately, that attitude, at least in its more strident forms, seems finally to be fading.

Nevertheless, catechists are likely to be asked to clarify just why a community based on love and rooted in grace needs a legal system. To that question, I have found no better answer than that offered by the Holy Father himself when he promulgated the 1983 Code:

The Code is in no way intended as a substitute for faith, grace, charisms, and especially not for charity, in the life of the Church. On the contrary, the purpose of the Code is to create such an order in the Church that, while giving primacy to love, grace, and charisms, it at the same time renders their entire development easier, both for the ecclesial society and for the individual persons who belong to it. (Pope John Paul II, Apostolic Constitution Sacrae Disciplinae Legis).

Catechists will certainly want to stress the great dependence which the 1983 Code of Canon Law places on the teachings of the Second Vatican Council. Indeed, in the same papal document cited above, Pope John Paul II called the revised code “a great effort to translate conciliar teachings into canonical language.” Elsewhere, the pope speaks of the importance of combining an understanding of Sacred Scripture, the juridic tradition of the Church, and the documents of the Second Vatican Council when applying modern canon law.

Since it is the purpose of any legal system to serve the community it governs, it stands to reason that the values of the Catholic Church must be the foundation of her canon law. While anything like a complete recital of the dependence of canon law on magisterial teachings would be too lengthy to attempt here, a few examples, taken at random, might give a flavor of this relationship between norms of belief and norms of behavior.

Canon 897, for example, opens the Code’s treatment of the Eucharist with a beautiful description of that august Sacrament as the source and summit of the Christian life. Canon 331, to choose another example, gives in one succinct paragraph the Church’s teaching on the primacy of the Roman Pontiff. Or again, Canon 1026 protects the freedom of those destined for ordination against being pressured toward or away from that state in life. The natural primacy of parents over their children’s education is upheld in Canon 793, and the ancient right of the faithful to have their cases brought to Rome for decision is preserved in Canon 1417. One can hardly open the pages of the 1983 Code of Canon Law and not find a provision important in helping the faithful understand their rights as believers or their obligations as members of Christ’s holy Church.

More Than Keeping the Law

Ironically, precisely because canon law is so clear in so many places about the expectations placed on the faithful of every station in Church life, there can be the temptation to assume that the mere satisfaction of canonical requirements is sufficient for the Christian life. This error, a form of legalism, is nothing but the flip side of the antinomian error mentioned above.

Catechists, therefore, will want to impress upon candidates for entrance into the Church that canon law is not the only source of rights and obligations in the Christian life. For example, moral law and natural law apply to us as Catholics, even though not every component of these laws is articulated in the Code. On a more mundane level, it should also be noted that not all of the written rules of Church law are found in the Code, liturgical law being a prime example of an important area of Church life regulated mostly outside of the Code.

Of course, being the product of man, the Code of Canon Law itself is neither perfect in its formulations nor complete in its anticipation of ecclesiastical issues. It will often be necessary and proper, therefore, to have resort to competent Church authority (whether papal, episcopal, or otherwise) to determine what kind of action is best under specific circumstances.

I hope these brief remarks will enable parish catechists to respond more confidently to some of the most common questions posed about canon law. Let me encourage, finally, catechists to make use of some resources mentioned herein to deepen their own understanding of the riches contained in the 1983 Code of Canon Law, in order that, as Pope John Paul II stated, “there may there flower again in the Church a renewed discipline, with the consequence that the salvation of souls will be rendered ever more easily under the protection of the Blessed Virgin Mary.”

Dr. Edward Peters has doctoral degrees in canon and civil law.

No Comments