St. Hildegard of Bingen

In this 14 minute podcast, Dr. Italy discusses the inspiring life of the great f...

A Witness of Christ in the Church:

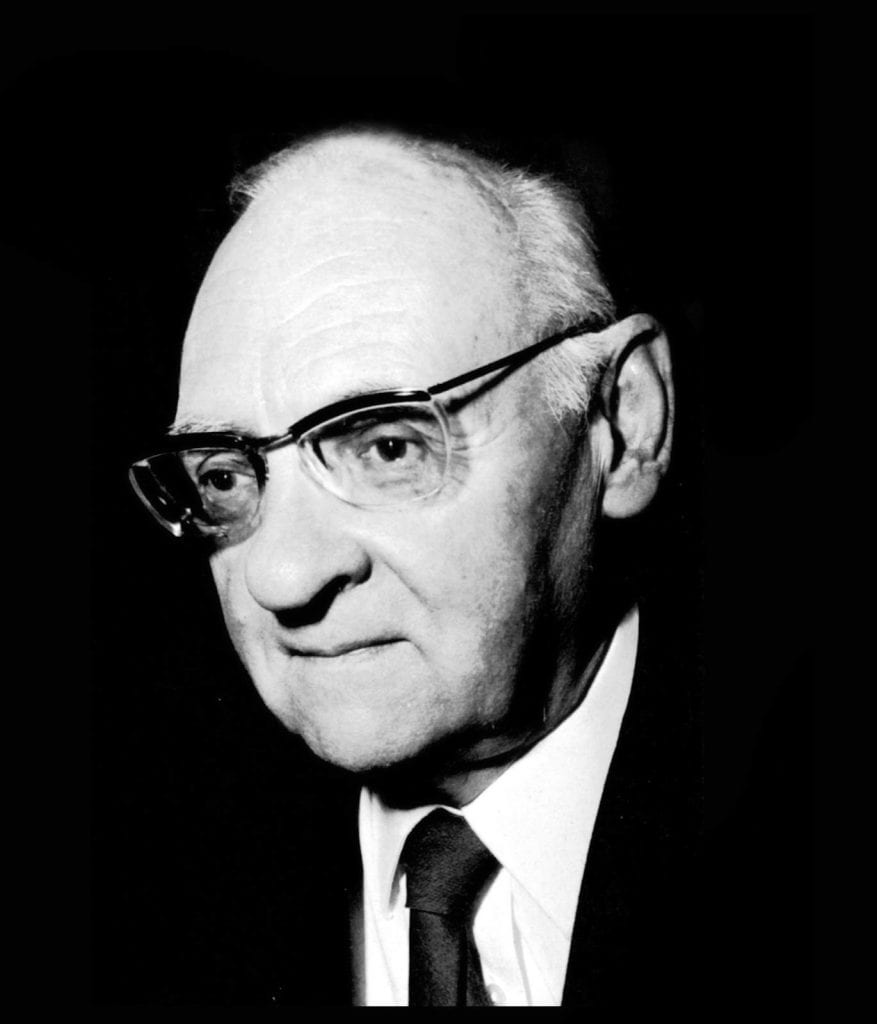

Hans Urs von Balthasar

by Henri de Lubac, S.J.

As Ludwig Kaufmann has justly remarked in a recent issue of Orientierung, it is disconcerting that from the first summons of the Council by John XXIII, it did not seem to have occurred to anyone to invite Hans Urs von Balthasar to contribute to its preparatory work. Disconcerting and — not to put a tooth in it — humiliating, but a fact that must be humbly accepted. Perhaps, all in all, it was better that he should be allowed to devote himself completely to his task, to the continuation of a work so immense in size and depth that the contemporary Church has seen nothing comparable.

For a long time to come the entire Church is going to profit from it. Indispensable though such things undoubtedly are, Hans Urs von Balthasar is not a man for commissions, discussions, compromise formulas, or collective drafts. But the conciliar texts that resulted from them — of Vatican II and of all previous councils — constitute a treasure that will not be yielded up at a single stroke: the councils are the work of the Spirit, and so these texts contain more than their humble compilers were conscious of putting in them. When later the time comes to exploit this treasure it will be seen that for the accomplishing of this task no work will be as helpful and full of resource as that of von Balthasar.

One thing we see immediately: there is not one of the subjects tackled by Vatican II that does not find a treatment in depth — and in the same spirit and sense as the Council — in his work. Revelation, Church, ecumenism, priesthood, liturgy of the word, and eucharistic liturgy occupy a considerable portion. Valuable insights on dialogue, on the signs of the times and the instruments of social communications will also be found…. Before the Fathers of the Council had insisted that the dominant role of Christ be recognized in the schemas on the Church and revelation, von Balthasar had seen the need. His voice was an advance echo, as it were, of the voices that were raised in St. Peter’s to ask for an adequate statement of the role of the Holy Spirit. The Virgin Mary in the mystery of the Church, her prototype and anticipated consummation, is one of his favored contemplations. Gently, but with all the force of love, he has denounced those eternal temptations of churchmen, “power” and “triumph”, and has at the same time recalled to all the necessity of witnessing through “service”.

His spiritual diagnosis of our civilization is the most penetrating to be found. Though it would be going too far to claim that he had produced a complete outline of the famous Schema 13 (Gaudium et Spes), he did, certainly, anticipate its spirit when he shows how “in the same way that the Spirit calls the world to enter into the Church, so he calls the Church to give herself to the world”; and he warns us that no good will come of a facile synthesis of the two.

In many cases one would also find in his writings the means to avoid the pitfalls of false interpretation which inevitably follow upon a call to aggiornamento. (We should state straightaway that he has courageously declared war on certain wild abandons that are a betrayal of the Council. Had more allies rushed to his flag, he would have had no need to write certain rather savage pages).

And if, finally, one is seeking (always in line with the Council) the doctrinal framework needed before beginning the dialogue with the non-Christian religions and the various forms of modern atheism, one can safely go to von Balthasar.

His work is, as we have said, immense. So varied is it, so complex, usually so undidactic, so wide-ranging through different genres, that its unity is difficult to grasp, at least at first blush. But, strangely enough, once you have got to grips with it, the unity stands out so forcefully that you despair of outlining it without betraying it. It is like a radiant impulse penetrating from a central point to all corners of his work.

With the astonished perception of the immense culture he enjoys, displayed without pedantry, must go equal appreciation of the strong judgment that dominates this culture. The reader has to appreciate the breadth of thought that is never narrow or doctrinaire even when it had to be (or believed it had to be) hard and trenchant; and yet, at the same time the reader has to fell the rigorous balance of doctrine that is, in both senses of the word, profoundly catholic. And our problem does not end there: the reader must also be brought to see that he is never confronted with a purely theoretical construction; nor is von Balthasar a polisher of systems. Author of numerous books, some of them very long, neither is he a book factory! Every word he writes envisages an action, a decision. He has not the slightest time for “that certain economy of the mind which budgets and spares itself”: everything is squandered that the “personal meeting” with God may be arrived at without delay.

This man is perhaps the most cultivated of his time. If there is a Christian culture, then here it is! Classical antiquity, the great European literatures, the metaphysical tradition, the history of religions, the diverse exploratory adventures of contemporary man and, above all, the sacred sciences, St. Thomas, St. Bonaventure, patrology (all of it) — not to speak just now of the Bible — none of them that is not welcomed and made vital by this great mind. Writers and poets, mystics and philosophers, old and new, Christians of all persuasions–all are called on to make their particular contribution. All these are necessary for his final accomplishment, to a greater glory of God, the Catholic symphony.

Many of his books are historical studies or translations or anthologies: he likes to remain in the background of the pictures he commissions to serve as witnesses of the truth of man or of God. He was twenty-five when he published his first work, Apokalypse der deutschen Seele, which was a historical commentary of the whole of German thought. A new edition has since appeared. Another book was an anthology of Nietzsche.

He has written commentaries on the Epistles of St. Paul to the Thessalonians and the pastoral Epistles. He has published his own translations of many of the Fathers: Irenaeus, the Apologists, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, Augustine. To several he has devoted a special study that in each case gave new life to its subject: Presence et Pensee, for instance, on Gregory of Nyssa; Kosmische Liturgie on Maximus the Confessor. He has given us a commentary on part of Augustine’s De Genesi ad letterum, and also on part of the Summa Theologica(Questions on Prophecy).

His translations include the revelations of St. Mechtildis of Helfta, the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius (whose devoted disciple he is), the Carnets Intimes of Maurice Blondel — as well as the greater part of Calderon’s religious drama. His incomparable translation of the lyric poems and Le Soulier de Satin of Claudel are well known.

He had done critical studies on Martin Buber and R. Schneider, on Peguy and Bernanos (Le Chretien Bernanos was one of the last books the Abbe Monchanin read in the summer of 1957 at Kodaikanal). The substance of a book (recently reprinted) which is a confrontation of the Protestant Reformation and Catholicism he owes to his close contacts with a neighbor in Basel, Karl Barth.

He has discussed the message of the two French Carmelites, Elizabeth of Dijon and Therese of Lisieux. The second volume of the monumental work he was long engaged on, Herrlichkeit, consists of a series of twelve monographs in which Denys and Anselm meet Dante and John of the Cross, Pascal and Hamann meet Soloviev and Hopkins….

Without ever abdicating his freedom to criticize, he is at ease with all, even those whose genius might appear most foreign to his own; but when the time comes to disagree with them he does not hesitate. He excels at highlighting the original contribution of each. He admires human wisdom wherever he finds it — but surpasses it. Sensitive to man’s Angst, he emerges from it in faith. The light from so many ancient sources allows him to illuminate the present situation and the accumulated wisdom of the centuries allows him, if we maybe permitted the metaphor, to bury his arrows ever deeper in our present reality.

The inner universe he introduces us to is thereby in its marvelous variety, perfectly unified. As in Tolstoy’s epic, a broad and calm atmosphere prevails; as in Dostoevsky, this atmosphere is electric with sharp spiritual insight. All is patterned around a lofty and unchanging notion of truth, outlined in his beautiful work Phenomenologie de la Verite. Truth is the cornerstone on which his theology of history is erected, more particularly in two essays. Finally, every word is designed to set in relief a basic anthropology relating to modern situations and the most pressing problems being faced by man today.

The contribution of the positive sciences is, perhaps, rather neglected, though scientific knowledge is assigned its proper place. The arts, it seems to von Balthasar, have more to offer by way of illuminating suggestion. He realizes, in fact, that the great works of art — and every great work is a work of art — go beyond so-called purely aesthetic categories and ought to be accepted, as they were conceived of by their artists, as efforts to complete a full image of man. Elsewhere he remarks that since the Renaissance, man is no longer thought of and understood in the cosmological context but in an openly anthropological one. And since “in an anthropological era the highest objectivity can only be attained by total engagement on man’s part”, we see the heightened dramatic character of all modern thought worthy of the name, a character that corresponds to the drama of existence itself.

Emerged from the cosmic development that nursed him, no longer in any way capable of regarding himself as one object among many, no longer having any home but his own fragility, man, von Balthasar thinks, is more predestined than ever “to become religious man” if he is to surmount this crisis of “dereliction” resulting from the new situation. His rapport with God acquires a sudden urgency; the biblical teaching of man made in God’s image becomes better delineated in his eyes and without the stage of natural knowledge being destroyed in the process the revelation of Jesus Christ presents itself to him more than ever as the necessary response to the interrogation forever carried on by his being. In his existence in time and history that constitutes “the visible explication of the existence-form of the God-Trinity”, Jesus comes to reveal this unknown that was in him to man; then “his features expand, are enlightened and deepened when he meets, not a mirror giving him back his own image, but his own supreme original”.

It is quite impossible to summarize here the theological thought of von Balthasar; we shall confine ourselves to the essentials. What distinguishes it and gives it its most striking originality is its refusal to be labeled. It can neither be termed old nor modern; it derives from no school and repudiates all piecemeal “specialization’. With no axe to grind, no single aspect of a given question is stressed to the detriment of the others, or rather, it refuses to delay over successive “aspects” while never forgetting to consider each.

The indispensable technicalities are there, whether in criticism (certain work on Origen, Evagrius, or Maximus, for instance, is inspired guesswork followed up by the most rigorous verification), or in dialectic (as in the dialectic “of the unveiling and enveloping” to different degrees of revelation, or in the relation of negative natural theology to the knowledge of the “face of revelation” which is given to us in Christ). But, for all that, it retains a highly synthetic character which breaks down the barriers to the interior life of things where the classic theology of our times is usually bogged down. While it does not offer direct pedagogical models, his thought — and even the form of his thought — may be usefully meditated on in view of the new directions which Christian thought must take since the Council.

Not to labor the point, let us say that in a word his theology, like our ordinary credos, is essentially trinitarian. Not that the Trinity fragments the divine unity — it is revealed to us, after all, through its work of salvation which is itself perfectly one. The “seamless coat” and the “lance’s thrust” are the symbols he uses to bring this home to us:

“A mystery that is broken up into aspects (epinoiai) will yield its secrets to the inquiring intelligence. But there is one mystery that absolutely refuses to do so, the irreducible mystery of the persona ineffabilis. From him the whole Church comes in his death, with the water and the blood — the Church which with all her truths, liturgies, and dogmas is only an emanation of the heart that broke unto death, as Origen better than anyone else understood.”

For the “thrust of the lance on Golgotha is in some manner the sacrament of the spiritual thrust that wounds the Word and so spreads it everywhere…. The Word of God cast into our world is the fruit of this unique wound.”

It is the Holy Spirit who ceaselessly introduces the Christian into the heart of this mystery. The Spirit’s role is to “refresh daily the memory of the Church and to supplement it in a renewed manner” with all truth. It is he who realizes everything in the Church and in her individual members “as it was he who formerly realized the Incarnation of the Word in the womb of the Virgin”. Also von Balthasar likes to point out the continuity between “the Marian experience” and “the maternal experience of the Church”. He likes to speak of “the Marian dimension of the Church” or of “the Marian Church”, and this simple expression we take as a condensation of his teaching which might also be said to be the teaching of the Church, or of the Virgin Mary, or of the Spirit, or of Christ, or of the Christian life.

His refusal of all biased “modernity” is by no means a refuge from present problems and the responsibilities they impose. The theologian must transmit a truth which is not his own and which he must guard against alteration, but transmitting this truth and watching over change to new situations demands from him a real involvement:

“One sees this very clearly in the manner in which St. Paul transmits what had been confided to him. Anyone who would wish to insert himself without danger in the chain of Tradition and transmit the treasures of theology, almost as children who switch their hot buns from hand to hand in the hope of not being burnt, would be the victim of a sorry illusion, quite simply because thoughts are not buns, or rather because from the morning of Easter combat was joined between the material and the spiritual.”

This theology, so traditional, remains relevant today and indeed does not lack a certain audacity. Von Balthasar has recalled to the modern theologian the immense task that confronts him and that even demands that he give all his attention for the moment to the central core of the doctrinal question:

“The doctrines of the Trinity, of the Man-God, of redemption, of the Cross and the Resurrection, of predestination, and eschatology, are literally bristling with problems which no one raises, which everyone gingerly sidesteps. They deserve more respect. The thought of preceding generations even when incorporated in conciliar definitions is never a resting-place where the thought of the following generations can lie idle. Definitions are less the end than the beginning…. No doubt anything that was won after a severe battle will be lost again for the Church, which does not however dispense the theologian from setting to work immediately again. Whatever is transmitted without a new personal effort, an effort which must start ab ovo, from the revealed source itself, spoils like the manna. And the longer the interruption of living tradition caused by a simply mechanical transmission the more difficult the renewed tackling of the task.”

The boldness of such a program, we can see clearly enough, does not lead us onto perilous or uncharted seas; it does lead us to the living center of the mystery. Its primary concern is for completeness. Von Balthasar’s audacity is not an irresponsible appetite for novelty: it proceeds from a faith whose daring grows in proportion to the strength of its roots. He himself is one of those men of whom he has spoken, men who devoted the work of their lives “to the splendor of theology — theology, that devouring fire between two nights, two abysses: adoration and obedience”.

The denials and lack of comprehension of our age disconcert few people as little as him. Fashionable opinion does not intimidate him; he never entertains the temptation to water down the vigorous affirmation of doctrine or the rigorous demands of the Gospel. There is no trace in him of that terrible inferiority complex rampant today in certain milieux among many Christian consciences. The Church, he has written, following St. Jerome and Newman, “like the rod of Aaron, devours the magicians’ serpents”; and by her, at the same time, he says in an image borrowed from Claudel and which might also be described as Teilhardian, “the key of the Christian vault is come to open the pagan forest”.And so von Balthasar has done. With calm assurance he displays to all, as far as he can, the entire Christian treasure. He does not hesitate to oppose, not criticism nor psychology nor technology nor mysticism, but all their unwarranted pretensions, and no one can accuse him of blaspheming what he does not know.

He knows the value of “human sciences”, he admires their conquests but will not submit to their totalitarian claims. His many observations on scriptural exegesis, on the need for a spiritual intelligence, and, in particular, on the blindness of a certain historico-critical method of dealing with the meaning of the history of Israel and the person of Jesus, all deserve a wider audience. “The Holy Spirit”, he writes, “is a reality which the philologists and philosophers of comparative religion are ignorant of or at least ‘provisionally put into parentheses’.” Von Balthasar removes the parentheses, or rather, he shows us how the Holy Spirit himself removes them.

Some of his criticisms — they are rare — might appear harsh. In every case they arose from his concern not to compromise essentials. He is too far above pettiness, too heedless of passing modes and allurements–particularly those that arise from pseudo-science or a frivolous faith — not to find himself often isolated. In the end however his attitude is always positive. His “tough line” is the same as that he has pointed out in Christ, the revealer of love. He is being true to his own position when he warns us of the dangers of isolationism. He does not wish “through enthusiasm for the glorious past of the Church”, or for any other reason, that the Christian “forsake the men of today and tomorrow. Quite the contrary. It is the duty of all who represent Jesus Christ — be they bishops or layfolk — to keep open their perspective on the human; never to allow any maneuver to push them back into isolationism or negative attitudes.”

“We live in a time of spiritual aridity.” The vital equilibrium between action and contemplation has been lost, to the apparent profit of the first but, for the very same reason, to its detriment. Von Balthasar has tried to reestablish this equilibrium. All his work has a contemplative dimension and it is this above all that gives it its profundity and flavor.

He introduced again into theology the category of the beautiful. But make no mistake, this is not to say that he surrendered the content of the Faith to current notions in secular aesthetics. (He had already said in Le Chretien Bernanos:”There exists a theological, an ecclesiological aesthetic that has nothing at all to do with aestheticism. In it pure human beauty meets with the beauty of the supernatural”).

He began by restoring to the beautiful its position as a transcendental –t his beauty “which demands courage and decision at least as much as truth and goodness, and which may not be separated from its sisters without drawing upon it their mysterious vengeance”. He has not agreed with those theologians who based their work on the separation of aesthetics from theology. His “theological aesthetics”, however, is not an “aesthetic theology”; it has nothing to do with any aestheticism whatever. Moreover, in this mystery of the beautiful which men, not daring to believe in it, converted into a mere appearance, he sees, as in the biblical description of wisdom, the union of the “intangible brilliance” and the “determined form”, which requires and conditions in the believer the unity of faith and vision.

The beautiful is at once “image” and “strength”, and is so par excellence in that perfect “figure of revelation” who is the Man-God. Faith contemplates this figure and its contemplation is prayer. Von Balthasar has observed that wherever the very greatest works were produced there was invariably “an environment of prayer and contemplation”. The law is verified in an analogous manner even in the pagan domain:

“The proud spirits who never prayed and who today pass for torchbearers of culture vanish, with regularity, after a few years and are replaced by others. Those who pray are torn by the populace that does not pray, like Orpheus torn by the Maenads, but even in their lacerations their song is still heard everywhere; and if, because of their ill-use by the multitude, they seem to lose their influence, they remain hidden in a protected place where, in the fullness of time, they will be found once again by men of prayer.”

Jesus, “indivisible Man-God”, is at once the object and model of Christian contemplation. This is the burden of the great work, still uncompleted,Herrlichkeit. The idea is put into action in a book like The Heart of the World in which the heart of Jesus opens to us in a kind of lyrical explosion. It may be seen even better perhaps in Prayer, an introduction to prayer that is at the same time a complete — the most complete available — outline of the Christian mystery. We shall restrict ourselves here to quoting just one passage, a passage of great value in that it provokes reflection on the primordial importance of contemplation in the life of the apostle:

“All we have been able to attest to other men, our brothers, of the divine reality comes from contemplation; of Jesus Christ, of our Church. One cannot hope to announce in a lasting and effective manner the contemplation of Christ and the Church if one does not oneself participate in them. No more than a man who has never loved is capable of speaking usefully of love. Even the smallest problem in the world will not be solved by one who has not met this world; no Christian will be an effective apostle if he does not announce, firm as the ‘rock’ Peter, what he has seen and heard: ‘We did not bring you the knowledge of the power and advent of our Lord Jesus Christ on the warrant of human fables, but because we have been privileged to see his majesty. He received from God the Father honor and glory…. This voice (of the Father) we have heard when we were with him on the holy mountain…'”

And he continues, not without sadness:

“But who today speaks of Tabor in the program of Catholic action? And who speaks of seeing, hearing, or touching that which all the zeal in the world cannot preach and propagate if the apostle himself has not recognized and experienced it? Who speaks of the ineffable peace of eternity beyond the conflicts of earth? But also, who speaks of the weakness and obvious powerlessness of crucified Love whose ‘annihilation’ to the extent of becoming ‘sin’ and ‘accursed’ has given birth to all strength and salvation for the Church and mankind? Whoever has not experienced this mystery through contemplation will never be able to speak of it, or even act according to it, without a feeling of embarrassment and a twinge of conscience, unless, indeed, the very naivete of such a basically worldly business has not already made this bad conscience apparent to him.”

(He has also, most opportunely, pointed out the danger of a “liturgical movement” which would be “isolated and uncontemplative”, just as he has also indicated his “contempt” for a war that has been declared against the contemplative tendency and that is sometimes waged in the name of eschatology).

On specifically Christian contemplation von Balthasar’s judgment is equally lucid: “All the other unfathomable depths to which man’s contemplation may penetrate, when they are not expressly or implicitly the depths of the trinitarian, human-divine, or ecclesial life, are either not real depths at all or are those of the devil.”

There is a kind of spiritual pride that is the most dangerous inversion of all; many so-called “mystical” states are no more than “artificial paradises” and as for those “sublime spirits” who search for the way apart from or above the humanity of the Savior, “what they experience in their ecstasies is the disguised ghost of their empty nostalgia”. Even in the Christian spiritual life it maybe opportune to recall that “the Gospel and the Church are not dionysiac: their overall impression is of sobriety; elation is left for the sects.”

These reservations do not, however, tend in the slightest to “crush the Spirit”. The Spirit must be received in the manner in which he gives himself, in a sort of tension between precision and enthusiasm:

“The saints knew how to do it: it is precisely this precision of the image Jesus as projected by the Spirit that they would wax enthusiastic about; and then their very enthusiasm, expressed with precision, would convey to all the fact that they had been gripped by this image. Even if they were full of indubitable truths that might express for all the world the truth of the Gospel, the saints were not arid textbooks: expressing the truth was the very life of the saints gripped by the Holy Spirit of Christ.”

Even for the humblest and weakest Christian it is in the simplicity of his Yes of acceptance and openness, in imitation of the Yes said by Mary to the Word, that the element of contemplation, inserted at the base of every act of faith by the Holy Spirit, is developed.

No matter what subject he is treating, and even if he never mentions any of their names, it is very clear that von Balthasar was formed in the school of the Fathers of the Church. With many of them he is on more than familiar terms; he has in many ways become almost like them. For all that, he is no slavish admirer: he recognizes the weaknesses of each and the inevitable limitations that result from the age in which each lived. With his customary frankness he criticizes even those he admires and loves most. But their vision has become his own. It is principally to them that he owes his profound appreciation of the Christian attitude before the Word of God.

He owes them too that vibrant feeling of wonder and adoration before the “nuptial mystery” and the “marvelous reciprocation of contraries” realized by the Incarnation of the Word. He is indebted to them for that sense of greater universality (in the strictest orthodoxy) because “it would appear at first that the infinite richness of God contracts and centers in a single point, the humanity of Jesus Christ … but this unity reveals itself as capable of integrating everything”.

This rhythm of reflection that combines confidence in received truth with a wide-ranging scope in investigation is also patristic. It is in spontaneous imitation of the Fathers that in him “the crystal of thought takes fire in the interior and becomes a mystical life”. They have communicated to him their burning love for the Church: for them, as for him “the Church is the exact limit of the horizon of Christ’s redemption just as, for us, Christ is the horizon of God”. This is why he considers it as futile to stress the many human faults “which are only too clear to anyone who looks”, as it is vital “to bring to light the admirable secrets of the Church which the world does not know of and which scarcely anyone wishes to recognize”.

The study of the “Church of the Fathers”, in Newman’s phrase, has confirmed him in an attitude as distant from “false tolerance” as it is far from “confessional narrowness’, so that his work, to anyone who wishes to meditate on it, offers a profound ecumenical resonance. One of the great apostles of ecumenism, Patriarch Athenagoras, recognized as much when he sent a messenger to Fr. von Balthasar with a gift of the gold cross of Mount Athos. We may also be glad that as the Faculty of Protestant Theology at Edinburgh University had already done, the Faculty of Catholic Theology at the University of Munster asked him in 1965 to accept an honorary doctorate.

It seems that von Balthasar has felt a certain shared situation with that of the Fathers, not in any archaic sense, but in that he too seeks to harness all the features of the culture of his time to make them achieve their full flowering in Christ — though he does not forget, any more than the Fathers did, that all the “spoils of the Egyptians are of no use and could, in fact, become a deadly burden if they are not received into a converted heart. For it is not the greatest knowledge or the deepest wisdom that is right but the greatest obedience, the deepest humility; not the sublimity of thought, but the effective simplicity of love.”

Effective simplicity are the key words if we are not to give a false idea of where this theologian would wish to lead us: he is theologian only to be apostle. For him, the task of theology, as Albert Beguin has written, “is ceaselessly to refer back into humble practice the full significance of the revealed word”.

We must confine ourselves here to his written work. As we have already insinuated this work is not narrow or inbred; its “Pauline passion” makes this very clear. Nothing pleases the author more than to wean his words away from dreams, from the illusion of some “spurious eternity”, to immerse them in the “true temporality” which is the process of configuration to Christ by submission,hic et nunc, to his Gospel. This is shown in one of his latest works, a short treatise with the Kierkegaardian title: Wer ist ein Christ?

The other element of his makeup, besides the Fathers, is the influence of St. Ignatius of Loyola. The need for total commitment to the following of Christ and for fidelity to what one has received from him, these two great themes of the Spiritual Exercises were revealed to him by his teacher, Erich Przywara, in all their force. His own ever deeper study of the Exercises has strengthened this conviction, which he is forever communicating to others.

Read, for instance, his booklet, published some fifteen years ago, Laicat et plein apostolat; follow it up with the splendid chapter he contributed to the symposium Das Wagnis der Nachfolge – “Zur Theologie des Ratestandes”. One may, if one wishes, pass over the concrete plans for a secular institute proposed in it; such things are contingent, depending on circumstances of time and place and personal likes and dislikes. But at this moment, with so many clamoring voices whose Christianity seems marginal arising in the bosom of the Church, those who are troubled and anxious at the sight of all the spray in the wash of the great vessel, the Ecumenical Council, even if they have no stomach for the deeper reaches of his greater works, will find much comfort in this essay that recalls, so objectively and precisely, the laws of the Gospel. It will also show them what the true dignity of the layman is, in Christ.

They will also better understand why the Council decided to include in the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, as though to contribute to the definition, the two chapters on the universal call to sanctity and on the externally organized spiritual life: just as the Old Testament was not confined to preparing men for the coming of Christ but also had the role of unfolding, even before the event, the dimensions of his person, so, and even more so, the Church does not restrict herself to the instruction of men with a view to the final return of Christ, but announces that his imprint must be placed on all creation, that a movement is under way which will end only under new skies and in a new land.

“She is not only on her way to this event; as the ‘mystical parousia’ she is its beginning.” And as for those who are determined to be true imitators of Christ in their apostolates, they will find themselves forewarned against the discouragement lying in wait for them when they hear the author say that for these true imitators, “Christian suffering will not be spared.”

Effective simplicity, we were saying, of love. This last is not a word von Balthasar pronounces lightly: he feels its full weight. Even before he reckons up the conditions for a Christian to realize it, he sees the human impossibility of it. How could man love man? He would “perish at the stifling” contact:

“If in the other person nothing is offered but what one already knows fundamentally for oneself — the limitations inherent in his nature, his anguish before them, his constant buffeting by them: death, sickness, folly, chance; a being to whom this anguish can give wings to the most astonishing discoveries — why should the ‘I’ lose itself for a ‘Thou’ which the ‘I’ cannot honestly believe is, at the deepest level, any different from itself? No reason at all, of course! If in my like it is not God I meet; if, in love, no breath of wind brings me the sweet scent of the infinite; if I cannot love my neighbor with any other love than that arising from my finite capacity; if therefore, in our meeting, that great reality that bears the name of love does not come from God and return to him — beginning the adventure is not worth the trouble.

It rescues neither from his prison nor his solitude. Animals can love one another without knowing God because they have no consciousness of themselves. But as for those beings whose nature permits and forces this reflection, and who have learned to practice it so profoundly that not only an individual but all humanity can look itself in the face, for them love of another is impossible without God.”

But Jesus came and, having promulgated his great commandment, diffused his Spirit:

“The Fathers of the Church and the medievalists were at considerable pains to explain why his coming was so late. We, on the contrary, ask why he did not delay his arrival till today when existence on this planet has become insupportable without him. Be that as it may, the seed he sowed pushes its way above the ground and becomes visible.”

The hour of history has sounded when it has become evident that man cannot be loved except in God — and that God is only loved in “the sacrament of our brother”. It is also the hour when it must be recognized — Jesus himself was explicit on this subject — ‘that all Christian love implies a bursting out of enclosures and inner precincts, an outgoing to the world, to him who does not love, to the lost brother, to the enemy.’ The Church is the Spouse of Christ but will not be acknowledged as such except in the transcendence that is her love.Glaubhaft ist nur Liebe. In all that it is most intimate and pressing, Christian love surpasses ‘Christianity’ but this very action of surpassing is Christianity itself.

And it is also God himself:

“… If the supreme reality in God were truth, we should be able to look, with great open eyes, into its abysses, blinded perhaps by so much light, but hampered by nothing in our flight towards truth. But love being the decisive reality, the seraphim cover their faces with their wings, for the mystery of eternal love is such that even the excessive brilliance of its night cannot be glorified except in adoration.”

We have barely touched on some of the many themes this immense achievement offers for our consideration, barely indicated some of its characteristics. We must now try to penetrate the secret of this highly personal thought, but whose personality consists solely in a loving search for an objective grasp of the mystery. Our reward (if we are successful) will be a heightened consciousness of the unique originality of our faith and, by that very fact, of every effort of the intelligence which wishes to be faithful to it. Since we cannot fully explore the whole, let us at least point out one of the avenues that leads to its center.

The precise nature of von Balthasar’s invitation to us to look on the face of Jesus is conditioned by a rather rigorous interpretation of the Christological formula of Chalcedon. The “density of the human nature” of Christ is altered not a whit by its union to the divinity, no more after the Resurrection than during the earthly existence — and the personal unity is not so less perfect that the man Jesus is not the face expressive of God. “Not for a single instant is the glory of God absent from the Lamb, or the light of the Trinity from that of the incarnate Word”. it follows that for the Christian, negative theology, even when pushed to its extremes, is not detached from its base, the positive theology that illumines that face.

No doubt, for him as for all, the divinity is incomprehensible: Si comprehenderis, non est Deus / if you comprehend, it is not God. The dissimilarity between the Creator and the creature will always be greater than the similarity. But the situation of the Christian is still not much different from that of the philosopher or any other religious man. He knows that God himself has a face. What appears in Jesus Christ “is the Trinitarian God making himself visible, an object of experience; the face in revelation is not the limit of an infinite without face, it manifests an infinitely determined face.”

In Jesus the believer sees God. For him, therefore,

“what is incomprehensible in God no longer proceeds from a mere ignorance; it is a positive determination by God of the knowledge of faith: the daunting and stupefying incomprehensibility of the fact that God so loved the world that he gave us his only Son, that the God of all plentitude lowered himself not only in his creation but in the conditions of an existence determined by sin, destined for death, removed from God. Such is the obscurity that appears even as it hides itself, the intangible character of God that becomes tangible by the very act of touching him.”

That cannot any longer happen in Christianity what “cannot but happen”everywhere else: “that the finite is, in the last analysis, absorbed by the infinite; the non-identical snuffed out by the identical”; religion devoured by mysticism. Accomplished “once for all”, the humiliation of God in the Incarnation cannot be nullified. In the tension manifest in the face of Christ “between the grandeur of a free God and the abasement of a loving one”, “the heart of the divinity” is opened before the Christian’s eyes.

The entire trinitarian teaching and all theology of revelation are bound up with this central vision; they explain one another through it and are themselves necessary for its understanding. As is normal, while the mind gives its consent to all this by an intuitive impulse, it makes the intelligence alert, satisfies it, and finally, like all fruitful thought, poses it more problems than it answers….

To finish what we set out to do we shall make another brief incursion, not this time to the core of the doctrine, but to the heart of the spirituality that corresponds to it. (Need we say that our efforts are no substitute for personal reading of his works.) A single word defines this spirituality: it is a spirituality of Holy Saturday.

“There was a day when Nietzsche was right: God was dead, the Word was not heard in the world, the body was interred and the tomb sealed up, the soul descended into the bottomless abyss of Sheol.” This descent of Jesus into the kingdom of the dead “was part of his abasement even if (as St. John admits of the Cross) this supreme abasement is already surrounded by the thunderbolts of Easter night. In fact, did not the very descent to hell bring redemption to the souls there?” It prolonged in some manner the cry from the Cross: Why have you abandoned me? “Nobody could ever shout that cry from a deeper abyss than did he whose life was to be perpetually born of the Father.”

But there remains the imitation of Christ. There is a participation, not only sacramental, but contemplative in his mystery. There is an experience of the abandonment on the Cross and the descent into hell, and experience of the poena damni. There is the crushing feeling of the “ever greater dissimilarity” of God in the resemblance, however great, between him and the creature; there is the passage through death and darkness, the stepping through “the somber door”. In conformity to the mission he has received, the prayerful man then experiences the feeling that “God is dead for him”. And this is a gift of Christian grace — but one receives it unawares. The lived and felt faith, charity, and hope rise above the soul to an inaccessible place, to God. From then on it is “in nakedness, poverty and humiliation” that the soul cries out to him.

Those who have experienced such states afterwards, more often than not, in their humility, see nothing in them but a personal purification. True to his doctrine which refuses to separate charisms and gifts of the Holy Spirit, the ecclesial mission, and individual mysticism, von Balthasar discerns in it essentially this “Holy Saturday of contemplation” by which the Betrothed, in some chosen few of her members, is made to participate more closely in the redemption wrought by the Spouse. We have arrived at a time in history when human consciousness, enlarged and deepened by Christianity, inclines more and more to this interpretation.

The somber experience of Holy Saturday is the price to be paid for the dawn of the new spring of hope, this spring which has been “canonized in the rose garden of Lisieux”: “is it not the beginning of a new creation? The magic of Holy Saturday … Deep cave from which the water of life escapes.”

Reading so many passages where this theme is taken up, we discern a distress, a solitude, a night — of the quality, in fact, as that experienced by “the Heart of the world” — and we understand that a work that communicates so full a joy must have been conceived in that sorrow.

Postscript: It is hard to believe that ten years have passed since these pages were written. They were meant as a testimony and not as an exposition or critique of von Balthasar’s writings. Had they been meant as such, how inadequate they would have proved to be! And how much less adequate they would be today!

In these ten years a monument has grown up before our eyes. As soon as the first volume of the projected triptych, Herrlichkeit, was achieved, work on the second volume was immediately begun. Apart from the prodigious quantity, the greatness of the work becomes more and more evident, even though the author’s modesty makes him shun the marketplace of publicity. Despite the silent hostility that superiority invariably encounters, and despite the remarkable resistance of certain professionals to take note of this unclassifiable man and acknowledge him as one of their own, even in France, where translations are regrettably few, haphazard, and sporadic, appearing at a desperately slow pace, von Balthasar’s thought has captured one by one the spirit of an elite youth.

Looking at von Balthasar’s work as a whole, among the many traits which cannot be all described here, I discern two main characteristics that have stood out in the course of the past decade and that seem to become more momentous and more consequential to the present.

First: instead of engaging in a series of a posteriori skirmishes with diverse presentations of Christian origins by contemporary writers, or being content to dissect them one by one to reveal the frequently chaotic excesses, von Balthasar grasps their essence in one glance with astonishing acumen. He takes hold of them, so to say, in one fell swoop which in itself is an intellectual feat — and then, with keen discernment comes up with an altogether different and unexpected view.

The person of Jesus, shining with radiant beauty, has an unmistakable affinity with the original interpretations of the evangelists writings. There is a reversion of perspective, an application of Newman’s method to an area that is even more fundamental than dogmatic development. The work is done with precision, with a spirit seeking understanding and rejoicing in what it finds. Never was the mysterious focal point, which is not the result but the source of unity, the unfathomable figure of Christ, the object of the Church Faith, made more clearly understandable to the historian.

Second: instead of, like many others, laboriously striving to rejuvenate scholasticism, for better or worse, by making gestures toward contemporary philosophy, or else abandoning, as so many others, all organized theological thought, von Balthasar shapes a fresh, original synthesis with radically biblical inspiration, without sacrificing any of the traditional dogmatic elements. His acute sensitivity to cultural developments and to the problems of our own times give him the necessary courage to do so.

His intimate knowledge witnessed to by his previous works — of the Fathers of the Church, of St. Thomas Aquinas, and of the other great spiritual writers, enables him to engage in this venture. He was nurtured by these great men and he follows in their footsteps, without servility and without falsification, because he has fully assimilated their substance. His enterprise is a far cry from the sporadic and futile experiments which bear the earmarks of subjective fantasies, or which, spawned by resentment against Tradition, secularize the tenets of the Faith or minimize them to the point of vanishing.

These two fundamental characteristics, described here somewhat awkwardly and certainly very sketchily, seem to me the more remarkable as they exactly answer the two basic insufficiencies of Christian thought today, and also because their beginning antedates the last Council’s invitation to theology to start its own aggiornamento. It is a mark of great and necessary works to arise in this manner, unnoticed at first, without even the initiator himself perceiving their future import. They take shape and develop as if by natural growth and not by command.

The twofold aspect of von Balthasar’s approach described above does not compromise the divine origin of Christian faith and the authenticity of Christian theology. Rather, the first is placed into a new light and the second is freed of naturalistic and “objectivistic” consequences which in modern times have often burdened and even disfigured it. The irrepressible vitality of Tradition sweeps away scared conservatism. It is a fact that for nearly a century all attempts to complete the codification of scholasticism and seriously to renew it were stopped authoritatively. So much so, that today it seems to be withdrawn from circulation.

Because of the magnitude of this phenomenon it would be futile to measure particular injustices. But it might be of historical interest to note that even if such an effort of discriminating discernment were made, it would not be capable of awakening new life. The debate held over this great body dissected it as a corpse, and many feel that they now face a great void. Still, few doubt that a new structure will arise in the service of an intact and renewed faith, which will salvage from our squandered heritage what was most valuable. And yet, even the admirers of von Balthasar’s works more often than not see merely a series of stimulating and beautiful books, written on important subjects that are more or less timely. They miss seeing their true import.

Nevertheless, with the passing years Hans Urs von Balthasar emerges more and more clearly as what he always has been: a man of the Church, in the most beautiful sense of the word. And in the present trial of the Church torn asunder by her own children, in a crisis the seriousness of which cannot be underestimated anymore by anyone–no matter what interpretation they may give it or whatever current phraseology they may use — von Balthasar, with sensitive awareness, accepted from God the role that his quality as a theologian demands. As a result, marginally to his great theoretical works but not marginally to his essential plan, he wrote a series of small volumes, simple and accessible but not less important or less personal.

For the same purpose also his long and tenacious effort to create that International Theological Review, which under the title Communio endeavors to contribute to and strengthen the intellectual and spiritual vitality of Catholicism. For this also the many humbler works, sermons, intimate instructions, and communications.

All these reflect a virile strength of thought and, together with an unfailing serenity, a liberated, free spirit. Von Balthasar is sincerely seeking, is never discouraged, is always conciliating. He faces all situations with a generously understanding intelligence, and his heart is open to all who approach him.

“I feel as if I had always known him”, said a recent visitor the day after their first meeting, surprised by the friendly reception that he received. And he added the picturesque words with which I shall conclude: “I felt as if I were walking with one of the Church Fathers who somehow wandered into Switzerland, and who counts among his ancestors the three Magi besides Wilhelm Tell…”

Telegram from Pope John Paul II

It is my particular desire, after manifesting my sincere sympathy at the sudden death of the esteemed Professor Hans Urs von Balthasar, to show the deceased, on the occasion of his burial services, a final honor through a personal word of commemoration.

All who knew the priest, von Balthasar, are shocked, and grieve over the loss of a great son of the Church, an outstanding man of theology and of the arts, who deserves a special place of honor in contemporary ecclesiastical and cultural life.

It was my wish to acknowledge and to honor in a solemn fashion the merits he earned through his long and tireless labors as a spiritual teacher and as an esteemed scholar by naming him to the dignity of the cardinalate in the last Consistory. We submit in humility to the judgment of God who now has called this faithful servant of the Church so unexpectedly into eternity.

Your participation at the solemn funeral services, very reverend Cardinal, will be an expression of the high esteem in which the person and the life work of this great priest and theologian are held by the Holy See. With all who commemorate him in sorrow and in gratitude, I beg for the dear departed eternal fulfillment in God’s light and glory. Now that his earthly life is completed, may he, who was for many a spiritual leader on the way to faith, be granted the vision of God, face to face.

In spiritual union, I impart to all who participate by their prayers in this liturgy for the deceased, from my heart, my special apostolic blessing.

At the Vatican, June30, 1988,

John Paul II

No Comments