Regina Caeli – Queen of Heaven, Rejoice!

The Regina Caeli, Latin for “Queen of Heaven,” is a hymn and prayer ...

An intro to Hippolytus of Rome whose work, the Apostolic Tradition, reveals intimate details of the life of prayer, worship and liturgy of the Roman Church in the late second century.

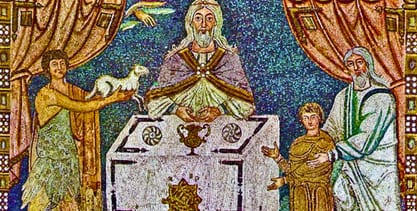

The most prolific Roman Church Father of the third century, St. Hippolytus wrote in an age when the Church of Rome was still Greek in language and culture. He was, in fact, the last Roman theologian to write in the language of the New Testament. And because the use of Greek died out in Rome by the mid fourth century, many of Hippolytus’ works were forgotten and even lost. Among those that survive is the earliest known Christian biblical commentary, the Commentary on Daniel (ca. 204), which accepted as canonical the parts of the book (Dan. 13-14) later rejected by some Protestant Reformers. His numerous other commentaries illustrate that, like the Fathers generally, he was before all else an interpreter of Scripture.

Hippolytus also shares with many Fathers another passion–the refutation of heresy. Several of his writings attack Gnosticism and pagan Greek philosophy. Others inveigh against Sabellianism, that Christian heresy which so emphasized the unity of God that any real, eternal distinction between the three persons of the Trinity was denied. In combating Sabellianism, however, Hippolytus ironically fell prey to the opposite extreme. His error, known as Subordinationism, tended to portray the Father and His Word as two altogether separate and unequal beings.

Ordained a priest under Pope Victor (189-197), Hippolytus unfairly accused Victor’s successor Zephyrinus (198-217) of Sabellianism. To his jaundiced eye, the Pope and his close advisors were liturgical as well as doctrinal innovators who relaxed the Church’s penitential and liturgical discipline. This motivated Hippolytus to write a brief treatise called the Apostolic Tradition (AT) which aimed to remind Roman Christians of the way of life and worship handed down from the apostles. This document, lost for over a millennium, was only recovered in the early years of the 20th century. Though written around AD 215, it most likely reflects the Roman practices of the late second century to which its traditionalist author wanted the church to return. The unmistakable Jewish imprint on the Christian liturgy it describes is striking evidence that these rites date back to a time when the leaders of the Christian Community were converted Jews, namely, the apostolic (30-65 AD) or sub-apostolic (65-100 AD) periods. Thus this work, true to its name, provides us an unparalleled window into the prayer and worship of apostolic Christianity.

One of the first things to note is how devoid Hippolytus is of any sola scriptura mentality that would pit the Bible against unwritten traditions. His devotion to Scripture, demonstrated in his commentaries, does not preclude his devotion to tradition, since both are for him expressions of the same apostolic teaching (AT 1:3-5; cf. 2 Thess. 2:15). Secondly, it is clear that, for Hippolytus as for other Fathers, the apostolic tradition is primarily identified with unwritten but time-honored liturgical practices rather than with unrecorded dogmatic facts such as Mary’s Assumption (cf. St. Basil, On the Holy Spirit 66).

Yet these liturgical practices presume and express important points of doctrine. For example, the AT’s prayer for the ordination of a bishop shows us that the bishop was understood as the high priest of the community who is given sacramental power, through ordination, to forgive sins and offer the eucharistic sacrifice (AT 3.4-5; cf. 1 Clement 40 and 44). Indeed, while private Bible reading (AT 36.2) and gatherings for biblical teaching (AT 35.2) are part of the rhythm of Church life, the Christianity of the AT is primarily a sacramental religion centering in liturgical worship led by the bishop. Here we are given clear evidence for a distinct rite of anointing with chrism (confirmation) by the bishop following baptism (AT 22) as well as for the baptism of infants (AT 21), two practices rejected by many Protestants as late distortions of pure apostolic Christianity. Sacramental blessing of such objects as oil (AT 5) and water (AT 21), are also discussed.

The earliest version of the Roman Baptismal Creed (later developed into the Apostle’s Creed) is found here (AT 21) as is the earliest complete eucharistic prayer (AT 4:4-13) which, incidentally, serves as the basis of Eucharistic Prayer 2 of today’s Roman Mass. Even the preface dialogue, which still survives in all Catholic Eucharistic rites, is found here verbatim: “The Lord be with you. And the people shall say: And with thy spirit. Lift up your hearts . . .” (AT 4.3). Not only is the Eucharist spoken of repeatedly as an oblation or sacrifice (AT 3.4, 4.2, 26.23), but the consecrated loaf is clearly believed to be the “Body of the Lord” (AT 26.2) to be treated with the greatest reverence (AT 32.2).

The Catholic practice of making the sign of the cross is encouraged: “And when tempted always reverently seal thy forehead with the sign of the Cross. For this sign of the Passion is displayed and made manifest against the devil if thou makes it in faith, not in order that thou mayest be seen of men, but by thy knowledge putting it forward as a shield.” (37.1). This text shows that the liturgical Christianity of the AT is not an empty ritualism; the exterior sign of the cross is not a superstitious substitute for faith but an outward expression of it. And faith, according to the AT, is not understood as something separable from outward expression. If the conduct of baptismal candidates has not changed after a period of instruction, this shows that they “did not hear the word of instruction with faith” (AT 20.1-3) and should be dismissed.

A few years after AT was written, Hippolytus and a small band of followers withdrew from the Roman Church, evidently claiming Hippolytus to be the rightful Pope. This schism was finally healed ca. 235 when the pagan emperor exiled Pope and Anti-Pope alike to the mines of Sardinia where they were apparently reconciled before dying together as martyrs. While Hippolytus was led to the point of schism by his rigid and judgmental “traditionalism,” those today who are tempted to travel the same road would do well to learn from him.

First of all, Tradition for him was not a matter of preserving the exact wording of certain prayers: the eucharistic prayer he provides is, he says, only a model since celebrants in his day could still compose their own prayer extemporaneously as long as the meaning was orthodox (AT 10.3-5).

Secondly, he reminds us that the original language of the Roman liturgy is not Latin, but Greek. The reform of the liturgy following Vatican II was not the first time that there has been significant liturgical change in the Roman Catholic tradition. When Pope Damasus converted the Roman liturgy into the new vernacular–Latin–ca. 380 AD, it was not a simple translation, but a thorough overhaul. While the basic structure and meaning of the liturgy remained the same, very little survived of the AT’s liturgical wording and style beyond the words of institution and the preface dialogue. In other words, fidelity to the apostolic tradition has always involved an interplay between continuity and the freedom of the Church to adapt to new cultural circumstances, an interplay that is most fittingly governed by the successors of the apostles themselves to whom, through sacred ordination, has been given the same Spirit which was given to the Apostles (AT 3.3).

The Apostolic Tradtion of Hippolytus reveals much of the worship, prayer, and liturgy of the early Church. For further reading, see J. Quasten, Patrology, vol 2; L. Deiss, Springtime of the Liturgy; G. Dix, ed., The Treatise on the Apostolic Tradition of St. Hippolytus. Gregory Dix, ed., The Treatise on the Apostolic Tradition of St. Hippolytus of Rome. London: SPCK, 1963 and Marcellino D’Ambrosio, When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers (Servant, 2014).

No Comments