Regina Caeli – Queen of Heaven, Rejoice!

The Regina Caeli, Latin for “Queen of Heaven,” is a hymn and prayer ...

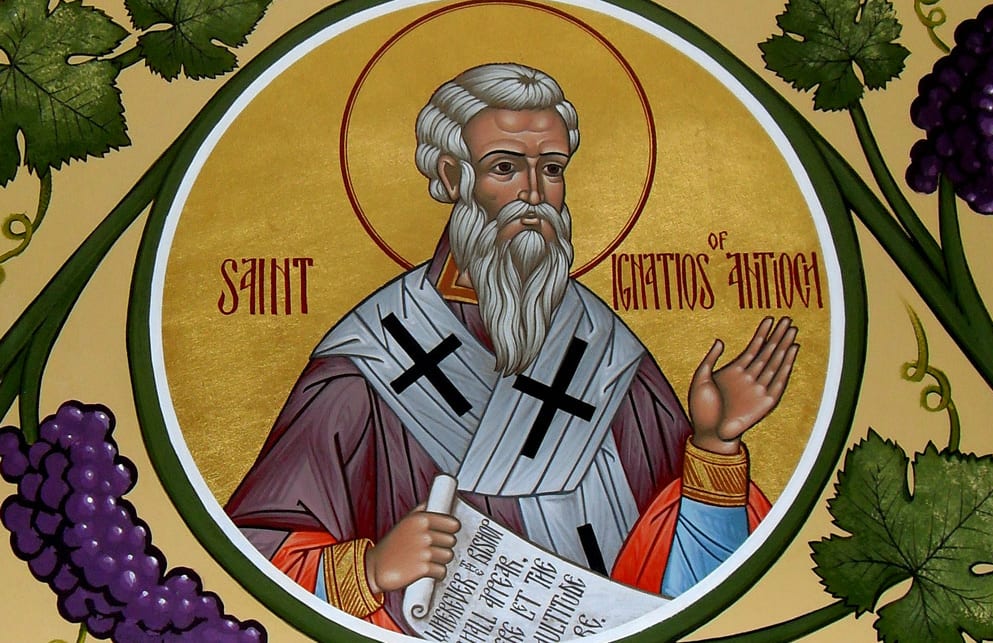

The writings of Ignatius, bishop of Antioch and one of the most inspiring of the Early Church Fathers, provide a revealing glimpse into the heart of an early Christian martyr as well as into the life and teaching of the Church just after the close of the New Testament era. He treats of the humanity and divinity of Christ, the Eucharist, and the hierarchical structure of what Ignatius calls “the Catholic Church.”

Sometime late in the reign of the Emperor Trajan (98-117AD), a persecution broke out in Syria. Ignatius, leader of the Christians in the region’s capital city of Antioch, was apprehended and condemned to die for his faith in the Roman amphitheater. Ignatius was chained to a brutal squad of ten Roman soldiers and marched overland through Asia Minor (modern Turkey) to Troas where he embarked upon a ship that, after various stops, eventually brought him to Italy and martyrdom.

Virtually all we know about Ignatius comes from seven brief letters penned while his party was stopped in Smyrna and later in Troas. Five of these letters were written to Churches in the province of Asia that had sent delegates to encourage Ignatius during his journey from Antioch to Rome. One was sent personally to Polycarp, bishop of Symrna, and the other is a moving appeal to the Church of Rome not to seek a commutation of his death sentence.

Ignatius was the second bishop of Antioch, the place where the followers of Jesus were called Christians for the first time (Acts 11:26; Eusebius Eccl. Hist. 3.22.36 and Origen, Hom. 6 In Luc). The importance of Antioch as a center of apostolic Christianity cannot be overestimated. Antioch was the first center of outreach to the Gentiles (Acts 11:20) and the base from which Paul and Barnabas were sent out on their missionary journeys (Acts 13:2-3; 15: 35-41; 18:22-23). Peter, too, spent some time in Antioch prior to relocating in Rome (Gal 2:11). Ignatius is therefore an important testimony to the way in which the teaching of these apostles was remembered by this eminent Church.

Yet his letters reflect not only the apostolic tradition as preserved by Antioch; many of the churches to which he wrote, such as that of Ephesus, were also founded by those of the apostolic generation. So the letters witness to a common apostolic patrimony as understood and lived probably only a decade or two after the writing of John’s Gospel.

Ignatius of Antioch speaks to a number of issues that have been disputed among Christians for centuries. Regarding the identity of Jesus Christ, St. Ignatius could not be more forthright in asserting his divinity. In the course of his seven letters he explicitly calls Jesus “God” (theos) a total of sixteen times (e.g., Eph. inscr, 15:3, 18:2; Ro. inscr , 3:3, Smyr. 10:1). There is no question of his meaning; he does not call Jesus God in a loose or merely honorific sense. Ignatius affirms that Christ is the invisible, Timeless (achronos) one, by nature incapable of suffering, who becomes visible and vulnerable to suffering through his human birth in time (Poly. 3:2). To call Christ “timeless” means that he cannot be the first and greatest created spirit, as Arius claimed in the fourth century and as the Jehovah’s Witnesses still maintain today. Rather, two hundred years before Constantine and the Council of Nicaea, Ignatius teaches that Christ is eternal, above time and all creation, God in the full sense of the term.

As emphatic as Ignatius is about Christ’s divinity, he is equally clear regarding Jesus’ true humanity. In his day there existed heretics called “Docetists” who believed Jesus’ body to have been a phantasm and his death therefore only an appearance. Against them Ignatius vigorously affirms the material reality of Jesus’ human flesh and the truth of his suffering and death (e.g., Symr. 1; Tral. 9).

In the course of his defense of Christ’s humanity, Ignatius demonstrates the early church’s realistic understanding of the Eucharist, which he calls “the medicine of immortality” (Eph. 20:2). In his mind, a denial of the real eucharistic presence flows from a denial of the incarnation. The Docetists, he says, “hold aloof from the Eucharist and from services of prayer, because they refuse to admit that the Eucharist is the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins and which, in his goodness, the Father raised. Consequently those who wrangle and dispute God’s gift face death.” (Smyr 7:1). For Ignatius and those to whom he writes, the Eucharist is clearly the center of the Church’s life (Eph 13:1) and can be validly celebrated only by the bishop or by one he authorizes (Symr. 8:2). And, in contradiction to such Judaizing movements as the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh Day Adventists, Ignatius says (Mag 9:1) that a distinctive mark of Christianity is to cease keeping the Sabbath (Saturday) and instead to observe the Lord’s Day (Sunday).

With regard to the nature and structure of the Church, Ignatius is a particularly important witness. He has a strong consciousness that Christians all across the world are united in one universal assembly which he calls “the Catholic Church” (Smyr. 8:2, the earliest instance of this phrase in surviving Christian literature). His letter to the Romans, an important witness to Peter’s presence and leadership in Rome (Ro. 4:3), acknowledges that the Roman Church ranks “first in love” (Ro, inscr.). While some would minimize the significance of this, it is hard to overlook the contrast between the salutation and tone of this letter and those of the letters written to the Asian Churches. The special esteem and deference shown by him to the Church of Rome demonstrates that some basic consciousness of the primacy of the Church of Peter and Paul existed very early in the second century.

Finally, for Ignatius and the Asian churches to which he writes, it is taken for granted that each local Christian community is led by a single bishop assisted by a council of presbyters (priests) and several deacons. According to Ignatius, “you cannot have a church without these” (Tral. 3:1). This is significant in light of the many Protestant Reformers who denied the apostolic foundation of different ranks of Christian ministers and accuse the Church of later times of inventing such a hierarchy. In fact many English Puritans rejected the letters of Ignatius as forgeries precisely because they believed it impossible for this degree of hierarchical structure to have existed at such an early period.

Indeed it is true that the Letters of Ignatius were interpolated in the fourth century and a number of later forgeries and legendary Acts of his Martyrdom were later added to them. But scholars in the late nineteenth century finally succeeded in establishing, beyond a reasonable doubt, the original text of the seven authentic letters mentioned above. And these texts show that Catholic doctrines as “the real presence,” Christ’s divinity, and a priestly hierarchy were not introduced by the Roman Emperor Constantine in the fourth century, as charged by the Jehovah’s Witnesses and others, but are part of the legacy bequeathed by the apostolic Churches at the close of the New Testament era.

This post focuses on the contribution of Ignatius of Antioch as a witness to apostolic tradtion regarding the humanity & divinity of Christ, the real presence of Christ’s Body and Blood in the Eucharist, and the Church as Catholic. For further reading on St. Ignatius of Antioch’s teaching on the humanity and divinity of Christ, the Eucharist, and the hierarchical structure of the Catholic Church, see J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, Johannes Quasten, Patrology, vol 1, Marcellino D’Ambrosio, When the Church Was Young: Voices of the Early Fathers (Servant, 2014), and Cyril Richardson, Early Christian Fathers (NY: Collier, 1970), whose translation of Ignatius’ letters is used in this post.

For a short video on Ignatius of Antioch, watch Ignatius of Antioch Martyr and Apostolic Father by Dr. Italy.

Banner/featured image Ignatius of Antioch by an unknown artist. Public domain.

No Comments