Pope Leo XIV – Inaugural Mass Homily

Elected on May 8, 2025, as the 267th successor of St. Peter, Pope Leo XIV’...

This post is also available in: Spanish, Italian

The parable of the merciless servant illustrates the meaning of “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us,” a petition included in the Lord’s Prayer. Anger can be righteous, but when we let it harden into resentment it becomes a poison that blocks the grace of God from flowing into us and through us. Forgiveness removes the block.

To LISTEN to this post read by Dr. Italy, click on the play arrow on the left, directly below this paragraph.

Just about everyone can recite the Lord’s Prayer from memory. That’s precisely the problem, though. We often rattle it off without really thinking about what we are saying.

“Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” Whenever we pray this line, we are asking God to forgive us exactly in the same way as we forgive those who hurt us. In other words, if we are harboring un-forgiveness in our hearts as we say this prayer, we are calling a curse down upon ourselves.

Let’s face it. We are all in desperate need of the mercy of God. But time and time again, the Word of God makes clear that the greatest block to his mercy is resentment. In the Old Testament, the book of Sirach (27:30-28:7) tells us how wrath and anger, cherished and held tight, are poisons that lead to spiritual death.

Jesus thinks this is so important that he includes a reminder of this lesson in the central prayer that he teaches to his disciples. And to drive the point home, he tells us the parable of the merciless servant, recorded in the Gospel of Matthew (18:21-35). As we listen to the story, we are incensed at the arrogance and hard-heartedness of someone who is forgiven a huge debt yet immediately throttles the neighbor who owes him a fraction of the amount he himself once owed.

Incensed, that is, until we realize the story is about us. For all of us who have ever nurtured a grudge are guilty of exactly the same thing.

Bringing up this issue is rather uncomfortable because we all have been hurt by others. Many have been hurt deeply. Think, for example, of the widows and orphans of September 11 and other acts of terrorism. Is it wrong to have feelings of outrage over such crimes? Does forgiveness mean that we excuse the culprit and leave ourselves wide open to further abuse?

Not at all. First of all, forgiveness is a decision, not a feeling. I think it rather unlikely that the Lord Jesus, in his sacred yet still human heart, had tender feelings of affection for those mocking him as his life blood was being drained out on the cross. But he made a decision, expressed in a prayer: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34).

In other words, there was no vindictiveness, no desire to retaliate and cause pain, suffering and destruction to those who delighted in causing him pain. Such desire for destructive vengeance is the kind of anger that is one of the seven deadly sins.

Notice that Jesus’ tormentors had not asked for forgiveness. Indeed they were still taking pleasure in causing him harm. Yet Jesus prayed to the Father for them, even making excuses for them – “they know not what they do.”

Image by Levan Ramishvili on Flickr. Public domain.

Did Jesus ever experience anger against those who sought his life?

Absolutely. Righteous anger is the appropriate response to injustice. It is meant to give us the emotional energy to confront that injustice and overcome it. Recall how livid Jesus was in the face of the Pharisees’ hypocrisy, because it was blocking the access of others to his life-giving truth. But notice as well that he overturned the money-changer’s tables, not their lives.

Forgiveness does not mean being a doormat. It does not mean sitting passively by while an alcoholic or abusive family member destroys not only your life but the lives of others. But taking severe, even legal action does not require resentment and vindictiveness.

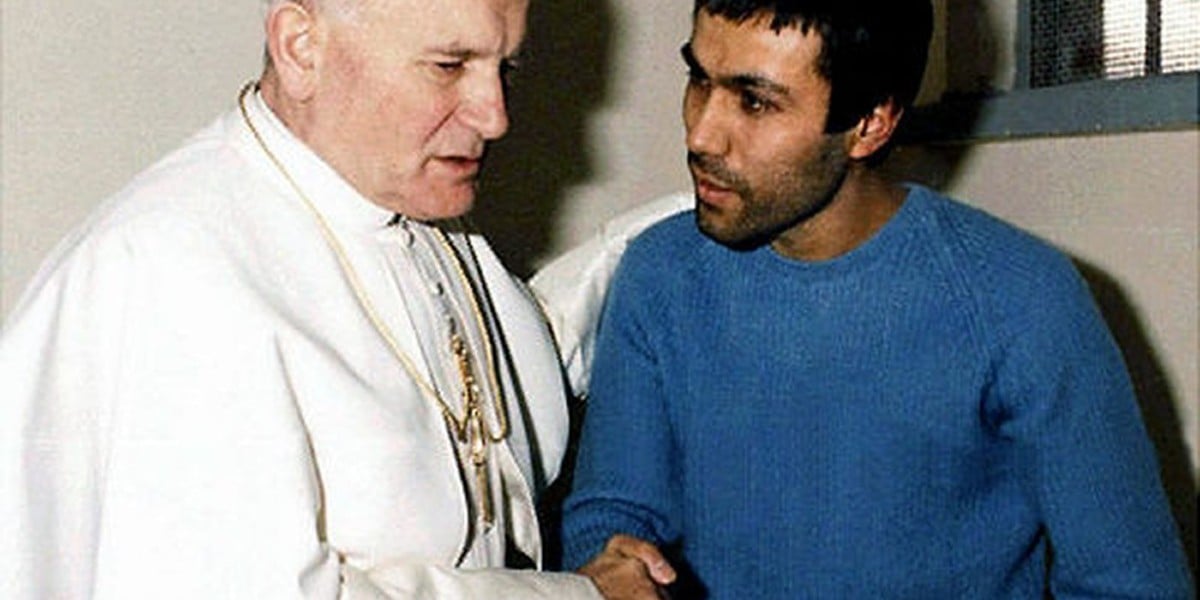

Pope John Paul II did not request the release of the man who shot him. But note that he visited him in prison to offer him forgiveness and friendship. In so doing, he stunned not only the assailant, but the whole world.

For more on the role of forgiveness in the Christian Life, see the DISCIPLESHIP Section of the Crossroads Initiative Library.

This post on forgive us our trespasses – forgiveness as an antidote to anger and resentment – is a reflection upon the parable of the merciless servant. This appears in the readings for the 24th Sunday in Ordinary Time, liturgical cycle A (Sirach 27:30–28:7), Psalm 103, Romans 14:7-9; Matthew 18:21-35, the parable of the merciless servant).

Banner/featured image by ANJALI SAHRAWAT on Scopio. Used with permission.

Adrian Johnson

Posted at 11:01h, 13 SeptemberEvery once an a while, we hear someone (perhaps ourselves) say, “I wouldn’t wish that (suffering or evil) on my worst enemy.” This is a good thing to say or think.

If you wonder if you have truly forgiven an enemy, one who has ruined your life and never been sorry much less asked forgiveness, visualise that evil and then your enemy. Would you truly wish that suffering on that miserable person who harmed you? If you wouldn’t, (though you have no fond feelings for them) then you have forgiven them.

As I used to tell my students– imagine your worst enemy can’t swim, but they’ve fallen into the stream above Niagra Falls, and they are drifting downstream yelling for help. There’s a long pole before you; all you have to do is extend it to them and they’re saved. Would your resentment of their past harm to you just see them fall to their death without lifting a finger, thinking “Drown, you SOB, you deserve it”? Most of the students looked thoughtful and said, “No.”

Loving your neighbour, –and forgiving him–, doesn’t mean liking or even wanting to be friends with him. It just means wishing him well, and not harm, and doing him good when you can (most of the time you can’t, unless to pray for him). Loving your enemy is easier than you think if you can separate your thirst for justice from your resentment of the one who has done you injustice.

Francis Fischer

Posted at 07:25h, 26 JanuaryVery insightful and helpful.

Hollis Liverpool

Posted at 12:24h, 13 SeptemberBeautiful thanks a million.

Fr. David Ullrich

Posted at 10:56h, 17 SeptemberExcellent example of forgiveness. I’ll use it on my prison mass today.